EXPLORE BOTSWANA’S OKAVANGO DELTA world heritage site with this slideshow, check the location map and get all the facts and information below.

For slideshow description see right or scroll down (mobile). Click to view slideshow

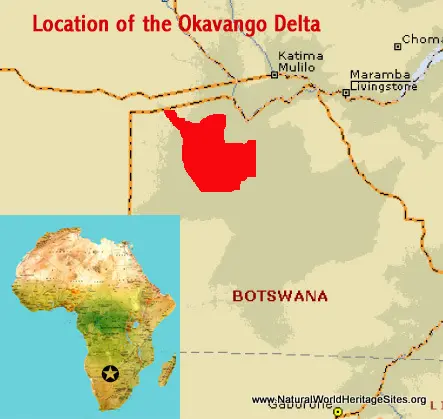

Location and Values: The Okavango Delta lies in the sand-filled Kalahari Basin in north-western Botswana. It is a vast inland delta, created by movements in the Earth’s crust which blocked the flow of the Okavango River some 40,000 years ago, forcing it to spread out across the Kalahari Desert sands. It has no outlet to the sea, so all its waters sink into the desert sands or are lost to evaporation.

The Okavango Delta is made up of permanent swamps, islands and seasonally-flooded grasslands which are a haven for wildlife. It is a natural oasis in which the perennial cycle of flooding activity continually maintains and shapes the ecosystem. Its waters originate in the highlands of Angola, arriving in the delta at the height of southern Africa’s dry season, providing a flush of new growth that attracts herds of elephants and grazing animals from a wide catchment area, at a critical time of year. There are few people, and the delta remains in pristine condition, mostly without roads or other forms of development. Moremi Game Reserve lies at the core of the world heritage site, with privately-managed Wildlife Management Areas making up most of the remainder. There are a number of luxury lodges within the Okavango Delta, most of which are only accessible by private air charter.

REVIEW OF WORLD HERITAGE VALUES: The specific attributes which qualify the Okavango Delta for world heritage status can be summarised as follows:

Africa’s most extensive inland delta without an outlet to the sea. The Okavango Delta is a huge inland delta, where the waters of the Okavango river disappear into the sands of the Kalahari desert without reaching the sea. The juxtaposition of this vibrant wetland and its arid desert surroundings is extraordinary and has led to it becoming known as the ‘Jewel of the Kalahari’.

Annual cycle of flooding. The annual flood-tide, which pulses through the wetland system every year revitalizes ecosystems and serves as a critical life-force during the peak of the area’s dry season (during June/July). As the flood-waters extend into lands around the wetland’s margins the pulse of new growth across the seasonal grasslands draws in herds of large herbivores, driving their migration patterns across a much wider landscape. In an extraordinary way plants and animals have adapted their life-cycles, growth and reproductive behaviour to the arrival of the flood-waters (as well as the arrival of seasonal rains, which allows dispersal to other areas as the waters of the delta recede later in the year).

Extensive pristine wetland with a wide diversity of wetland types in a continuous state of flux. The Okavango Delta extends over an area half the size of Belgium, with 6,000km2 of permanent swamps and 7-12,000 km2 of seasonally flooded grassland. Remarkably, it remains in a largely pristine condition, unaffected by any major developments either within the delta itself, or anywhere along the course of its inflowing rivers and their tributaries. The wetland ecosystem is in a constant state of flux as channels change their course, fires determine short-term grazing cycles and elephants impact trees and other vegetation.

Rich diversity of species across many taxa, with significant populations of African mega-fauna. The delta supports a high diversity of natural habitats including permanent and seasonal rivers and lagoons, permanent swamps with reeds and papyrus, seasonal and occasionally-flooded grasslands, riparian forest and woodlands, dry woodlands and island communities. Each of these habitats has a distinct species composition with strong representation of aquatic organisms across most taxa. A total of 1061species of plants (belonging to 134 families and 530 genera), 89 fish, 64 reptiles, 482 species of birds and 130 species of mammals has been recorded. The Okavango supports significant populations of wetland-adapted mammals such as sitatunga, red lechwe and southern reedbuck, and serves as a core habitat for part of Africa’s largest elephant population (with 200,000 individuals ranging across northern Botswana).

Habitat for important populations of rare and endangered species. The Okavango Delta provides a refuge to globally significant numbers of rare and endangered large mammals, including white and black rhinoceros, wild dogs, lions and cheetahs. It is also recognized as an Important Bird Area, harbouring 24 species of globally threatened birds, including six species of vulture, Southern Ground-Hornbill, Wattled Crane and Slaty Egret. Thirty-three species of water birds occur in the Okavango Delta in numbers that exceed 0.5% of their global or regional population.

Area of exceptional natural beauty with outstanding wilderness qualities. The natural beauty of the emerald-green ‘Jewel of the Kalahari’ in its red-sand desert setting is legendary. Its crystal clear waters meandering through the ever-changing channels of the delta, its islands and waterways teeming with wildlife create an unparalleled range of vistas of exceptional beauty. Furthermore, the size and difficulty of accessing the area (except by light aircraft) ensure that it maintains exceptional wilderness qualities with very little development or management infrastructure.

CONSERVATION STATUS AND PROSPECTS: The nature of the Okavango Delta – a vast inaccessible wetland on the fringes of a sparsely populated desert – gives it a high degree of natural protection. There are very few roads and tourism is built around a high-cost low-volume business model with small lodge facilities accessed by private charter aircraft. Human impacts across the delta are low and the area remains in a largely unaltered, pristine condition. The most significant long-term threat arises from the possibility of future use (or impoundment) of the waters of the Okavango River which flow from catchment areas in the Angolan highlands through Namibia before crossing into Botswana and reaching the head of the delta. Any such developments would be subject to the approval of all three government members of the Permanent Okavango River Basin Water Commission (OKACOM), which should ensure recognition and respect for the outstanding universal values of the world heritage site. The most significant existing management challenges arise from an observed decline in populations of some large mammals ( which has resulted in a nationwide hunting ban), a continued need to control alien plants, and to ensure proper management of local community access rights and benefit sharing.

MANAGEMENT EFFECTIVENESS: Overall the ecological integrity of the Okavango Delta remains good as a result of its large size, inaccessibility and low human population densities in surrounding areas. The legal basis for protection is adequate for Moremi Game Reserve (4,610 km2 or 23% of the world heritage ‘core area’) but weak elsewhere, with much of the area (15,625 km2) designated as ‘Wildlife Management’ and ‘Controlled Hunting’ Areas where human settlement, cultivation and livestock are (potentially) allowed. In practice most of the Wildlife Management Areas are well protected and managed by commercial tourism operators. Management regimes are complex and vary across the site according to the designation of particular ‘blocks’. There are significant constraints in capacity and resources for management of Moremi Game Reserve and across most of the community-managed WMAs.

REVIEW OF CONSERVATION ISSUES AND THREATS: The following issues represent specific threats to the ecology, conservation and values of the Okavango Delta world heritage site.

Poaching. The level of poaching affecting the Okavango Delta’s wildlife is unknown, but a 2012 aerial census of large mammals by Botswana’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks confirmed that there has been a significant decline in populations of some key large mammal species over the past decade (since a comparable survey was last done). An earlier NGO aerial survey (carried out in 2010) had suggested that populations of 11 animal species had plummeted by an average of 61 per cent (Gifford, 2013), with ostrich, wildebeest, kudu and giraffe particularly badly affected. Whilst the reason for the decline is not fully understood, some attribute it to over-hunting in parts of the delta that are designated as Wildlife Management Areas where commercial hunting was (until recently) allowed.

Resource use by local communities, including livestock grazing. Local people have rights to use certain natural resources within the Okavango Delta, including fish, reeds and thatching grass, medicinal plants and poles for house-building, as well as being allowed to keep cattle and other domestic stock in the area. The ecological impact of this is limited. The local communities include descendants of the original San hunter-gatherer inhabitants of the area, as well as more recent immigrants from other ethnic groups. As there are only three settlements (with a total population of 530 individuals) in the interior of the delta, resource use tends to be restricted to peripheral areas close to villages outside the core zone of the world heritage site.

Veterinary control measures including fences and chemical spraying of tse-tse flies. Botswana’s livestock industry has for decades depended on the prevention of disease transmission between wildlife and domestic stock through (1) the use of high multi-strand veterinary cordon fences to stop the movement of large wild mammals into livestock grazing areas, and (2) the eradication of tse-tse flies through chemical spraying. Most of the Okavango Delta is designated a ‘livestock free zone’, and its southern boundary follows a veterinary fence. This stops livestock coming into contact with wildlife, but it also blocks the traditional migration and dispersal of wildlife to the south. Other veterinary fences lie to the east and north of the world heritage site, but these have been abandoned (or removed) in recent years so migration routes towards the Makgadikgadi Pans (to the East), Chobe National Park, and other areas have been re-established.

Disturbance from tourism. Tourism in the Okavango Delta is necessarily a low-impact low-volume business, since there are no permanent roads into most of the area and everything has to be flown into small-scale tented camps and lodges within the delta. There are only about 2,000 beds in the core area of the world heritage site, and sound policies and procedures to regulate tourism are in place. Nevertheless, there are some localized problems related to tourism including the creation of illegal roads (particularly in Moremi Game Reserve), pollution and waste disposal, forest fires and disturbance of plant and animals (especially nesting birds). Most noticeably, noise pollution from low-flying aircraft and boats can be a nuisance, affecting the ‘wilderness experience’ of visitors.

Habitat destruction by elephants. About one third of Africa’s elephants – more than 200,000 individuals – roam across the border lands between the Okavango Delta and adjacent areas of northern Botswana, Namibia, Angola, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The population has grown significantly in recent years and is now causing serious habitat destruction (particularly in the mopane woodlands surrounding the delta).

Invasive alien species. The floating water fern, Salvinia molesta (native to South America) became established in the Okavango Delta in the 1980s and has become widespread. It chokes water channels and prevents light and oxygen penetration into sub-surface waters, impacting the aquatic ecology. A reasonable degree of success in controlling this invasive weed has been achieved through the propagation of a weevil (Cyrtobagous salviniae) as a bio-control agent, but Salvinia infestation remains a significant problem.

Uncontrolled fire. Fires are frequently and deliberately started by people throughout the Okavango Delta to (1) stimulate new growth for livestock grazing (2) improve stands of reeds and thatching grass, (3) attract wildlife to areas of new growth for tourist viewing, (4) clear access through the wetlands to fishing sites, and (5) clear agricultural land around the margins of the delta.

Upstream water extraction /impoundment. The most significant long-term threat to the integrity and ecological function of the Okavango Delta lies beyond Botswana’s borders in the catchment areas of Angola and Namibia, where upstream use of water or construction of dams could prove devastating. Namibia has already indicated an intention to connect its Eastern National Water Carrier to the Kavango River to ‘provide water to Windhoek and the surrounding areas’, and there will doubtless be many other demands on the waters of the Okavango as regional development gains momentum. There are reports of possible Chinese interest in irrigated agriculture in the river basin in southern Angola.

Climate change. The potential effects of climate change on the delta have been a research focus of staff at the Okavango Research Institute for several years. It seems likely that there will be some increase in evaporative losses of water in the delta due to increases in regional temperature, but other impacts of climate change are less certain. A drying of the catchment would result in the replacement of existing seasonally-flooded grassland with more wooded communities, reducing the overall size of the delta ecosystem.

Pollution and/or eutrophication of waters. The quality of the inflowing waters is just as important to the ecological integrity of the Okavango Delta as the volume of water and its flooding cycle. The possibility of pollution from diamond mining in the catchment areas of southern Angola has been identified as a potential future threat. Likewise, the proposed Chinese-backed irrigated agricultural scheme in southern Angola would not only result in water use, but could also lead to eutrophication and/or pollution with artificial fertilizers, pesticides and other agrochemicals.

Mining. Mining presents a significant potential threat to the Okavango Delta as a number of concessions overlap the world heritage site. The Government of Botswana has given assurances that mining will not be allowed in the core area of the world heritage site but there is nevertheless a possibility that it could be undertaken in the buffer zone, or areas of the catchment in Angola and/or Namibia.

Links:

Google Earth

Official UNESCO Site Details

IUCN Conservation Outlook

UNEP-WCMC Site Description

Birdlife IBA

Management Plan (2008, 216pp, pdf)

Slideshow description

The Okavango Delta slideshow starts with a series of aerial views of the landscape across the delta from south-east to north-west. It begins with a view of the dry red Kalahari sands that dominate most of northern Botswana outside the delta, before entering the swamps and showing the flooded grasslands, meandering rivers, islands, stands of papyrus and other swamp vegetation, game trails and other features of the Okavango Delta. Back at ground level, the water monitoring station at Shakawe is shown, as well as some of the ways people use the area’s abundant resources – bundles of cut papyrus (used for thatching), fishing, and tourist boating along one of the main channels of the inflowing river in the area known as the Okavango Delta ‘panhandle’. Some of the prominent wildlife species are shown – from waterfowl to ground hornbills, elephants, lions, zebra, kudu and hippos, as well as the specially-adapted swamp antelope, the red lechwe. Finally a glimpse of traditional community life and livelihoods in the Khwai Development Trust area on the fringes of the Okavango Delta is provided, where some intricate basket-ware is produced by highly-skilled local women.

Factfile

Website Category: African Wetlands

Area: 20,236 km2

Inscribed: 2014

Criteria:

- (vii) natural beauty,

- (ix) evolutionary processes,

- (x) biodiversity