EXPLORE THE CHITWAN NATIONAL PARK with this slideshow, check the location map and get all the facts and information below.

For slideshow description see right or scroll down (mobile). Click to view slideshow

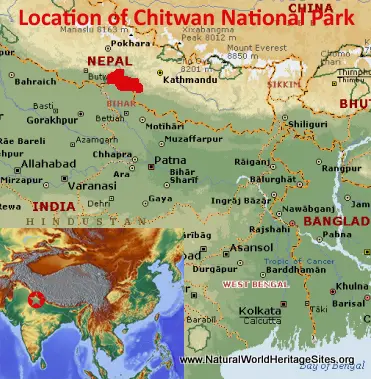

Location and Values: Chitwan National Park lies at the foot of the mighty Himalayas in south-central Nepal, and protects one of the last remaining examples of intact ‘Terai’ habitat. The park is globally important for conservation of the great one-horned Asian rhinoceros, one of the world’s most threatened large mammals, which thrives on Chitwan’s alluvial flood plains and adjacent forest. Chitwan has the second largest population of this iconic animal in the world (after India’s Kaziranga park) and conservation efforts here have been so successful in recent years that ‘surplus’ animals are now being translocated to re-establish populations in other Nepalese parks. In addition to rhinos, the park provides prime habitat for the endangered Bengal tiger, and other important threatened species including leopard, wild dog, gaur, sloth bear, Gangetic dolphin, mugger crocodile and gharial. As well as these biodiversity values, Chitwan’s inscription on the world heritage list recognizes the outstanding natural beauty of the ever-changing river landscapes set against the backdrop of its lush forests and the towering snow-capped peaks of the high Himalayas in the distance. It also recognizes the outstanding importance of ‘ongoing ecological processes’, particularly the ever-changing riverine habitats, floodplains and adjacent ‘sal’ forests, which are able to follow their natural evolutionary course, protected from human activities and intervention.

Conservation Status and Prospects. According to IUCN’s Conservation Outlook Assessment (2017) the conservation status of Chitwan National Park is of ‘significant concern’. The IUCN report notes that ‘ The management at Chitwan National Park has been successful in ensuring effective conservation over the last few years; as shown in the rapid increase in tiger and rhino numbers. Nevertheless, the site remains vulnerable to current threats such as pollution, invasive species and negative impacts of mass tourism, and to potential threats such as proposed road developments (including the Tarai Hulaki Highway), increasing human-wildlife conflicts, the impacts of climate change or earthquake or sudden and unexpected increases in poaching or the resurgence of political instability. As such Chitwan should remain on the radar of conservationists worldwide as an area of high concern – as well as an exemplar of effective management. However, under the new Constitution of Nepal of 2015, Rural Municipalities will be given more power in managing their resources, which may lead to increased challenges in the management of Chitwan National Park, which overlaps with four provinces.

Links:

Google earth

Official UNESCO Site Details

IUCN Conservation Outlook

UNEP-WCMC Site Description

Birdlife IBA

Slideshow description

The slideshow is intended to ‘tell the story’ of the Chitwan National Park, and features a portfolio of photos from a visit by Peter Howard in October 2017. One of the highlights of a visit to Chitwan is the opportunity to ride on elephant back, allowing a much closer approach to rhinos and other wildlife than would otherwise be possible, whilst also providing a high vantage point for viewing above the level of the dense cover of tall elephant grass. Elephants are used by park protection staff on patrol, but elephant-back riding by visitors is not allowed within the park. Instead the authorities have ceded control of adjacent forest land to local community ‘forest user groups’ who now protect forest resources for their own use. Rhinos and other wildlife have dispersed out of the park into these areas and trees have regenerated so that community groups are now able to benefit economically by offering elephant-back wildlife viewing to visitors. Many of the photographs in the slideshow are taken in the community-managed ‘Ghaila Ghari’ forest adjoining the northern boundary of the park. As with other such community forests, government has supported the installation of a game-proof fence on the ‘farm/village’ side of the forest (while the park side remains open) so that human-wildlife conflict is prevented. This approach has been highly successful in providing a ‘buffer zone’ for the core area of the park, and an economic incentive for conservation efforts.

There are no longer any hotels or lodgings inside the park, so visits to the park interior are restricted to daylight hours by jeep. Most visitors find accommodation outside the eastern boundary of the park at Sauraha, crossing the river by canoe and joining a 9-12 person ‘collective’ jeep safari at the river bank on the park side. There is also a (relatively new) road bridge linking communities to the north with the large ‘forest enclave’ village of Madi to the south of the park, and this bridge provides access for visitors undertaking jeep safaris from the northern side. There are relatively few jeep tracks, and the forest understorey is quite dense, so jeep safaris tend to be much less ‘productive’ in terms of wildlife viewing opportunities than elephant-back rides in the community forests. The slideshow provides a sense of what is likely to be seen during a jeep safari during October, immediately after the monsoon rains (by January visibility through the forest understorey is much better following extensive fires). Jeep tracks follow a circular route that takes in a number of small lakes (seasonally-flooded river channels and ox-bow lakes) and through the sal forest (named after the dominant ‘sal’ tree). Spotted deer, wild boar, rhino and rhesus macaques are amongst the mammals most likely to be encountered, while a profusion of birds can be seen especially at the waterside. Sloth bears are said to be quite common, while signs of tigers, such as claw marks on trees, or pug marks in soft mud are more likely to be seen than the animals themselves – but a couple of photos of tigers taken elsewhere are included in the slideshow.

The other worthwhile activity during a visit to Chitwan is a canoe trip on the Rapti River. The river is the most scenically attractive part of the park, with its ever-changing complex of islands, sandbanks, and cliffs set against the riverside vegetation of tall forests and grassy embankments. During a canoe trip visitors are likely to see a variety of conspicuous birds, including species such as open-billed storks, ruddy shelduck, cormorants, kingfishers and red-naped ibis as well as the two threatened crocodilians – the mugger crocodile and gharial. There are only about 235 gharials surviving in the wild, so this critically endangered animal is being bred in a captive breeding facility at Chitwan, for eventual release into the wild. The ‘Gharial Conservation Breeding Center’ at the park headquarters in Kasara is open to visitors and provides some interesting insights into the conservation challenges for this and other threatened species. Some photos of this breeding centre are included in the slideshow. Finally, an aerial view of the park, community forest and adjacent agricultural land is included, showing the very distinct boundary between land dedicated to intensive irrigated rice production alongside ‘fenced wild-lands’ dedicated to conservation. This extreme example of land-use regulation can also be explored in more detail by clicking on the Google Earth link alongside.

Factfile

Website Category: Tropical & Sub-tropical Savannas & Woodlands

Area: 932 km2

Inscribed: 1984

Criteria:

- Outstanding natural beauty (vii);

- Ecological processes (ix);

- Natural habitat for biodiversity (x);

- Significant number of rare, endemic and/or endangered species (x)