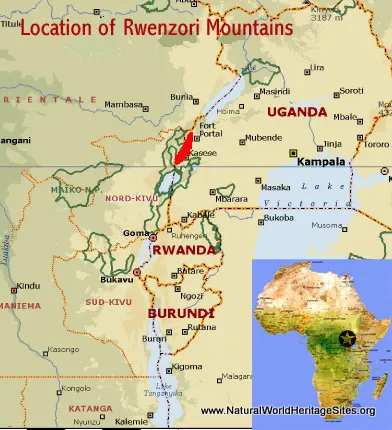

EXPLORE UGANDA’S RWENZORI MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK with this slideshow, check the location map and get all the facts and information below.

For slideshow description see right or scroll down (mobile). Click to view slideshow

Values: The Rwenzori Mountains are steep, rugged and very wet. They owe their origins to thrusting of the earth’s crust associated with the creation of the Albertine Rift, which makes them geologically quite different to the other high East African mountains (which are of volcanic origin). The Park covers most of the centre and eastern half of the range (the other side forms part of the contiguous Virunga park in DR Congo). It includes Africa’s third, fourth and fifth highest peaks in an alpine highland of glaciers, snowfields and lakes of astonishing beauty. It protects five distinct vegetation zones, many rare, endemic and endangered species, and the richest montane flora in Africa – a very unusual cloud forest of giant heathers, groundsels and lobelias, draped in cushions of luxuriant mosses. A comprehensive review of the world heritage values of the Rwenzori Mountains National Park is provided below, together with details of the area’s conservation status and the threats it faces.

REVIEW OF WORLD HERITAGE VALUES: The specific attributes which qualify this site for world heritage status can be summarised as follows:

Spectacular mountain scenery: The park protects some of Africa’s most spectacular mountain scenery, including Africa’s third highest peak (Mount Margherita, 5,109m), and an abundance of glaciers, lakes, snow-capped peaks, waterfalls and bog-filled valleys. Unlike most other high African mountains, the Rwenzori mountain range is not of volcanic origin but was created through tectonic movements in the Earth’s crust associated with the formation of the Western arm of the Great Rift Valley. The mountain range includes multiple peaks, and its location on the edge of the Congo Basin is associated with very high rainfall and the development of exuberant Afro-alpine vegetation with impressive giant Senecio and Lobelia plants growing in the high bogs, and great cushions of colourful moss perched on the leaning branches of giant heathers.

Rich montane flora, with many endemic species: The park has the richest montane flora of any site in Africa, including many endemic species. The heaths and Afro-alpine vegetation zones that extend from around 3,500m to the snowline (at around 4,400m) represent the rarest vegetation types on the African continent. Prominent constituents of this extraordinary vegetation are several endemic species of giant groundsels (Senecio) and Lobelias, which punctuate the landscape like giant candelabra.

Rare and endemic birds: Although the total number of species of birds recorded (217 species) is not especially high, the avifauna includes two Red Data Book species (Shelly’s Crimsonwing, Cryptospiza shelleyi, classified as Vulnerable; and Lagden’s Bush Shrike, Malaconotous lagdeni, classified as near-threathened), as well as 15 of the 24 species endemic to the Western (Albertine) Rift area of central Africa.

Rare and threatened mammals: The Rwenzori range is especially important for its rare and endangered mammals, including an unusually rich small mammal fauna and some prominent larger mammals. The small mammal fauna includes 28 species of rodent and 12 shrews, of which nine species are endemic to the western (Albertine) Rift and three (Micropotamagole ruwenzori, Paracrocidura maxima and Ruwenzorisorex suncoides) are extremely rare. Large mammals of conservation concern include elephants, chimpanzee, Rwenzori black-fronted duiker and l’Hoests monkey.

Diversity of habitats: There is an exceptional diversity of habitats on account of the range of altitude (2,100 to 5,100m), equatorial location and high rainfall. There are montane forest, bamboo, tree heather, Afro-alpine and Nival zones at increasing altitude, each with its own special characteristics and associated flora and fauna.

CONSERVATION STATUS AND PROSPECTS: The conservation outlook remains robust, given the natural attributes and resilience of such an inaccessible and rugged place, with its wide range of elevation, and linkages with other components of Africa’s most diverse trans-frontier protected area complex (particularly Congo’s adjoining Virunga National Park, another world heritage site). There remain significant uncertainties over the likely long-term impact of climate change, which may result in loss of the glaciers and snowfields by 2030 and have far-reaching long-term effects on plant community dynamics. Concern over the possible restoration of copper mining within the world heritage site remains, while other threats such as the growing impact of tourism, and low levels of illegal hunting are being addressed.

MANAGEMENT EFFECTIVENESS: The remote and rugged nature of the terrain ensures a high level of natural protection against unsustainable resource use, so the need for management intervention is limited. The park has a good current management plan, but implementation is falling short of expectations due to budget and staffing constraints. Visitor numbers and revenues are growing strongly but the park is still heavily dependent on international partners and donor support to cover recurrent and investment costs.

REVIEW OF CONSERVATION ISSUES AND THREATS: The following issues represent specific threats to the ecology, conservation and values of the world heritage site.

Climate change: Global warming is raising temperatures and melting the park’s glaciers. In the longer term climate change is expected to cause a general shift of vegetation zones to higher elevations reducing the area of the rare high-altitude Afro-alpine vegetation communities. At the same time it will increase the feasibility of cultivation close to the park boundary (on land that was previously too cold for most crops). There may be increased incidence of landslides and flooding if precipitation falls as rain instead of snow.

Staffing and budgetary constraints: Although the rugged and inaccessible nature of the park affords a high degree of natural protection against human influence, a higher level of management intervention could improve protection significantly. However, human and financial resources are inadequate and many of the provisions of the 2004-14 General Management Plan (GMP) have not yet been implemented. For example, the GMP envisages a total of 111 staff by 2014, but only 64 were deployed in 2011. Park revenues amount to about 50% of recurrent expenditure, with the balance contributed by donors.

Poaching: Low-level subsistence hunting is a way of life for the local Bakonjo people, and its impact is limited due to the extremely rugged terrain and difficulty of capturing prey species. Hunting is generally carried out with wire snares, and guns are not widely used in traditional hunting.

Agricultural encroachment: Affects only a few of the lower valleys and ridges, in the immediate vicinity of the park boundary. Elsewhere the land inside the park is too steep and inaccessible for cultivation, and the climate unsuitable. The soils are generally poor.

Buffer Zone degradation: A certain amount of cultivation is carried out close to the lower boundary of the property (which follows the 2,100m contour), but tends to be limited to cultivation of wheat on some of the ridge tops. Most of the local population lives in the valleys, quite far from the park, where they benefit from better access and better provision of services. The boundary is well maintained and marked with concrete beacons and a line of live marker trees.

Unsustainable use of minor forest produce: Minor forest produce, notably bamboo, natural fibres, mushrooms, honey and the like, make an important contribution to local livelihoods and these products may now be taken from designated zones under the terms of 14 community-use Memoranda of Understanding. Off-take is monitored by park rangers, but there are few data on which to base sustainability decisions and harvesting quotas.

Tree felling: The montane forests of lower elevations are not generally suitable for commercial exploitation, but a few trees are felled to satisfy local demand for building poles and sawn timber.

Impacts of tourism: Tourism numbers are still low compared with East Africa’s other great mountains – the drier, higher Mounts Kilimanjaro and Kenya. However, some areas are affected by unsustainable firewood collection; litter and waste management; and trampling of vegetation (especially through the extensive bogs).

Disturbance from use of local footpaths: The Rwenzori Mountains are the homeland of the Bakonjo people who occupy the lower slopes on all sides of the mountain, traversing the mountain to trade and exchange with other villages. Although this foot traffic is now much reduced (there used to be major coffee-smuggling routes through the mountains in the 1980s) there are still significant well-used footpaths across the mountain ridges of the northern spur, connecting Kabarole and Bundibugyo districts. These are associated with a certain amount of forest resource use and the presence of people may deter use of available habitat by some of the larger mammals such as elephant.

Subterranean copper mining: The Kilembe mine used to operate an extensive network of deep mine shafts extracting copper ore from strata in the Kilembe River Valley within the area now designated as the Rwenzori Mountains World Heritage Site. The mine was closed as a result of the economic difficulties which afflicted Uganda during the 1970s and 1980s and has never been re-opened. However, significant reserves of copper ore remain, and the Uganda Investment Authority was seeking bids for the assets of the holding company Kilembe Mines Ltd as recently as 2009.

Insurgency and security issues: The park is located in a volatile part of central Africa, with insurgency activity on both sides of the international border erupting from time to time. The park was closed to visitors and all conservation projects ceased for six years from 1998 to 2003 as a result of insecurity on the Ugandan side, and the property was inscribed on the List of World Heritage in Danger between 1999 and 2004. The park is now secure and tourism and management activities are unaffected by security concerns.

Links:

Google Earth

UNEP-WCMC Site Description

Official UNESCO Site Details

IUCN Conservation Outlook

Management Authority: UWA

Promotional NGO

WWF Project

Birdlife IBA

Slideshow description

The slideshow provides a comprehensive overview of Uganda’s Rwenzori Mountains National Park showing the area’s spectacular mountain landscapes and its wildlife habitats. Some of the characteristic plants and animals in each vegetation zone are illustrated, from the montane forests of the lower slopes, through the bamboo and tree heather zones to the alpine moorlands and the glaciers, rock and ice around the summit. Some of the conservation management issues, local community livelihoods and typical visitor experiences involved in hiking to the central peaks are shown.

Factfile

Website category: Mountains

Area: 996 km2

Inscribed: 1994

Criteria:

- (vii) aesthetic;

- (x) biodiversity